Many of us have experience how difficult it is to manage cultural change. This video outlines the importance of taking the unwritten rules into account to avoid that they become roadblocks in our change journey. The approach developed by Peter Scott-Morgan shows how to make these deeply rooted drivers of employee behavior visible and how to efficiently address them in our change journey (Peter Scott-Morgan: The Unwritten Rules of the Game, 1994)

Many cultural change initiatives fail – why?

Don’t you find it amazing how difficult it is to change the culture of a company? We want to make our organizations more agile, we want to empower the employees, we want to have more open and transparent communication. But again and again our change initiatives fail.

Usually this is not due to a lack of efforts. Communication and change plans are being put in place, we conduct cultural assessments, we promote new values and the company’s purpose. But the cultural change is very slow and sometimes does not happen at all. The old, entrenched ways of working continue to exist, as if nothing could alter them.

This difficulty to change the culture of our organizations is even more surprising when you think of all the great things that we achieve: our companies develop life-saving medicine, we drive the digital revolution, we develop highly sophisticated transportation and communication technologies etc. But these same organizations struggle to adjust their culture. Why is it more difficult to change our company culture than to develop such innovation? I believe it is worthwhile reflecting on this. The starting point of actually making change happen might be to understand what is specific about companies and company culture.

Companies are a compact network of human interactions

So let’s explore this a bit further. Let’s first acknowledge that our companies are quite compact and complex social systems when compared to other social systems such as a neighborhood or a sports club. Companies bring large groups of people together and coordinate their activities. The output of each one’s work is input for many others along the so called value chain. This requires close coordination. This complex network of interactions is governed by detailed policies and procedures. People play very different roles. We have decision makers as well as a number of supporting activities, etc. This creates a dense network of human interactions, where the behavior of each one has an influence on the whole organization. It’s a truly complex system of human interactions.

We use sophisticated tools – but they often fail when it comes to cultural change

Change management therefore addresses that behavioral part. The way we communicate, the way meetings are held, the way information is shared in the organization, etc. We usually also pay attention to the symbols that influence the way things are perceived in the organization. This can go as far as changing the office structure (e.g. to open space) or moving into a new building that represents better the kind of organization we want to be. Employee satisfaction surveys are used to collect feedback from employees on all these aspects. So we have a number of highly sophisticated tools at hand. But we nevertheless face the same challenge over and over again: changing our culture seems to take very long, often such change initiatives fail and we lack of levers to steer the change process.

The Unwritten Rules of the Game by Peter Scott-Morgan

I believe that the book “The Unwritten Rules of the Game” by Peter Scott-Morgan can help manage such change processes and make cultural change initiatives more successful.

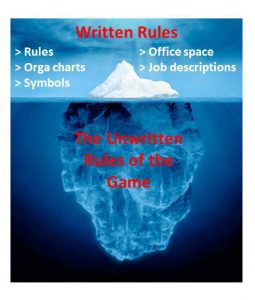

Let’s define first the written rules

Many explicit rules govern how people should act in organizations, which include job descriptions, the organization charts, delegation of authority, policies and processes etc. This visible part of the ice berg includes also the way office space is defined (who has what size of office? Who is sitting where? etc.) as well as the symbols that we use in our organizations (e.g. chat kind of charity do we support and what does that say about who we are as an organization? What rituals do we have in terms of company events? etc.). All of these aspects can be observed directly. They are visible. They are the emerging part of the iceberg.

What are these unwritten rules?

But according to Peter Scott-Morgan, there are also so called “unwritten rules” that govern people’s behavior and that are not visible. Everyone in the organization somehow knows them. They are part of the company culture. But they are not specified anywhere. These unwritten rules are also not the result of a curious decision making process (e.g. by management). They emerge in the organization by themselves. These unwritten rules are triggered by certain events (as we will see in the examples below) and they represent the interpretation that employees are making on how to best defend their own interests in light of these events.

This interpretation becomes part of the habits of the organization, of the tacit knowledge that employees have about how to operate efficiently. It becomes part of the culture. This means also that these unwritten rules are transmitted as part of that company culture to newcomers, who have not witnessed themselves the event(s) that triggered a specific unwritten rule. Over time, people in the organization will follow the unwritten rule, but without being conscious about where they come from. Let’s take some examples.

First example

Recently I interacted with a person who works in a company that is well known for its strong performance orientation. You would expect that in such an environment, risk taking is rewarded. But the contrary is the case. There is a habit of keeping long email trails so that you can identify the person to be blamed, if something goes wrong. Everyone in the company is following that unwritten rule without knowing why. But there is no doubt that some events from the past, where failure has been punished must have triggered this.

Second example

The way people communicate in an organization can often reveal unwritten rules. Let’s take the example a company that promotes open communication (explicit rule), but where everyone knows that bad news is not welcome (unwritten rule) and that you should rather use time with management to promote yourself instead of speaking about areas for improvement. Here we see that the official rule and the unwritten rules are antagonistic. This company might have an open door policy but in reality team members know that their manager wants to hear only the good news.

Third example

A company might promote learning from failure, but people remember that the CEO has killed a messenger, who has delivered bad news. This company might promote an open feedback culture, but it is known that in reality people should rather promote themselves and not point at areas for improvement, because they are otherwise perceived negatively.

Fourth example

The explicit rule in the company could also be that high performance is promoted, but in reality people know that it is better to change jobs regularly, so that you can be held accountable. Job hopping is here the unwritten rule.

How can the unwritten rules be detected?

As we saw earlier, everyone in the organization usually knows these unwritten rules, but they are deeply rooted in the company culture and therefore not visible. Peter Scott-Morgan has developed an interview approach that helps bring these unwritten rules to the surface. This is done through one-on-one interviews or group interactions, where 3 questions are discussed:

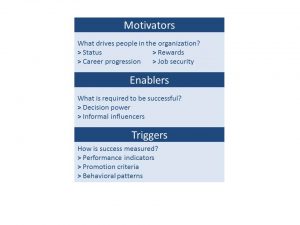

1) Motivators: What drives people in the organization? What are the rewards that the individuals working for the organization actually desire, e.g. more money, advancement, satisfying work, relaxed working conditions.

2) Enablers: Who is in a position to give out these desired rewards? Who has the power?

3) Triggers: How is success measured? What are the conditions which people perceive are necessary to achieve the motivators?

The answers to these questions will help identify the unwritten rules. They will allow going beyond what is the declared way of working and touch on “how things really work in this company”. That will allow coming up with a cartography of the culture and power structure of the organization as perceived by those within. It will help explaining these unwritten, but dominant rules.

The answers to these questions will help identify the unwritten rules. They will allow going beyond what is the declared way of working and touch on “how things really work in this company”. That will allow coming up with a cartography of the culture and power structure of the organization as perceived by those within. It will help explaining these unwritten, but dominant rules.

How to use that understanding of the unwritten rules to drive cultural change?

Let’s come back to our initial question. Why do so many cultural change initiatives fail? The answer that Peter Scott-Morgan brings is the following: Cultural change initiatives fail, if the proposed new rules of the game are conflicting with the existing unwritten rules (if they are antagonistic) and if this issue is not explicitly addressed.

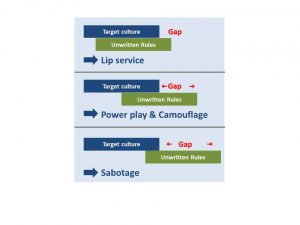

The graph here shows 3 level of antagonism between the proposed new culture and the existing one. It also outlines the likely employee reaction if that difference is not addressed explicitly in the change program.

In case of a slight difference, people will tend to pay lip service to the new culture without a real buy-in.

If the difference is bigger, we will be able to observe power-plays between those who want to implement the change and those who resist it. This power play will of course be hidden. You might for example have those who are in favor or against a certain new business line. This business development project will be used as a pretext for the power-play (camouflage).

In case of a strong antagonism between the established unwritten and the proposed new rules of the game you can observe examples of sabotage, where employees will let projects fail in order to defend the existing ways of working. That can go all the way to the suicide of organizations that are no longer able to adapt to the changes in their environment.

How to reconcile the unwritten rules and the proposed new rules?

The starting point is to understand the unwritten rules and to bring them to people’s attention. The second step is to assess the gaps between the existing rules and the proposed new rules and to be explicit about that difference. Once we know what unwritten rules are antagonistic to the proposed new rules, we can engage with the employees in the organization to convince them of the benefits of the proposed ways of working. True change of behavior can happen only once employees have made that conscious choice to accept the new rules.

Finally, it will be of crucial importance that top management is changing their own ways of working. They need to understand how their behavior has reinforced the old culture. They will need to be very consistent in the way they adjust their own behavior to support the new culture. They will be observed very carefully by the organization. Any gap between the proposed new ways of working and their actual behavior will immediately trigger new “unwritten rules”. Any leader who promotes the open feedback culture, but does not encourage team members to speak up will – as a matter of fact – block the cultural transformation himself or herself unconsciously. Full consistency is required and top management behavior has a strong impact on making the change happen.

Reading the book “The Unwritten Rules of the Game” by Peter Scott-Morgan can in my eyes be a great preparation to efficiently lead cultural change. It opens our eyes on what really drives people’s behavior. It shows that mastering the implicit rules is necessary to successfully manage cultural change.

Reference

Peter Scott-Morgan, The Unwritten Rules of the Game (New York: McGraw Hill, Inc., 1994)

More information in my book:

Sven Sommerlatte : Successful Career Strategy – An HR Practitioner’s Guide to Reach Your Dream Job (Springer, June 2023). ISBN: 978-3-662-66790-3